Fascia (pronounced ‘Fasha’) is a part of the connective tissue system that permeates, surrounds and connects your muscles, organs and other structures in the body. The connective tissue system comprises of fascia and other categories which include; blood, bone, cartilages and proper connective tissue. It’s helpful to remember that not all connective tissue is fascia, but all fascias are connective tissue. Perhaps surprisingly blood is classified as connective tissue, whereas muscle isn’t.

In simple terms, connective tissue has a fibrous element made of protein called collagen and a watery, gel-like element called the extracellular matrix (ECM) which is a large proportion of connective tissue as a whole. It is vitally important as it is the internal sea to which surrounds and supports all the various cells in your body. The ECM is vital for cushioning forces and mediating optimal intercellular processes.

Myofascial Release is a term commonly used to denote an approach to the manual therapy or ‘massage’. Its application can be described in general terms as ‘direct’ (firm application of pressure) or ‘indirect’ (a more subtle application of pressure). Both have benefits.

In this instance the manual technique I have developed is informed by an indirect approach and can with a variety of manual moves (vibration, light, firm or sustained pressure) involve both strong and light pressure where appropriate. It not only affects fascia, but the whole connective tissue system entirely.

Most of the fascia is made up of collagen and is fibrous in nature. It is helpful to imagine this fibrous element like a 3-dimensional web-like structure that enables structural and spatial architecture of the body to be maintained. This architectural system is connected entirely throughout the body and communicates on a ‘systems’ level, where every part influences the whole.

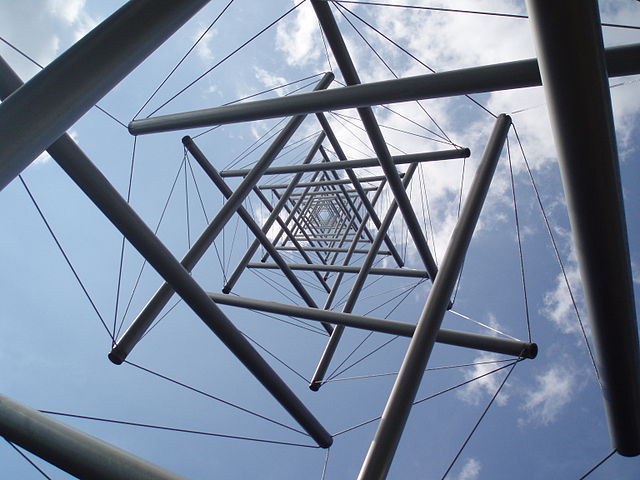

Tensegrity

One way of appreciating the modelling of the human body in relation to load mechanisms is ‘bio-tensegrity’; an architectural term adapted to biological systems with the work of Steven Levin. Originally it was the models of sculptor Kenneth Snelson that were elegantly capturing a structure that was both stable and maintained a constant, dynamic, spatial relationship inherent in its form.

Tensegrity structure

If applying the tensegrity model to the human form, it suggests the wooden elements are the bones ‘floating’ in an interconnected system of connective tissue (including the fibrous collagen) as the cables. Although a clunky metaphor, it is a far more complex than described, but more useful to understand the body in this manner rather than the ‘mechanical building block’ model that still to this day dominates.

The space that the connective tissue provides allows for regional and global connections in the body, with efficient transmission and absorption of tension during movement. These spaces in the body are fluid filled and maintaining this fluidity is crucial for the body to remain in optimal health.

Bio-tensegrity is increasingly recognised as a more sophisticated way to understand biomechanics, because it integrates anatomy from the molecular level to the entire organism, as Donald Ingber’s work in cell biology and bioengineering has demonstrated. In biomechanical terms the body is appreciated as an entire integrated system where the loads are distributed dynamically, creating multi-dimensional stability.

Effects on the connective tissue system

Over time, prolonged overloading, traumatic stresses, strain, chronic adaptive changes, or poor habitual movement patterns all exert stress on the connective tissue system. Your connective tissue then becomes desicated (dry) more rigid and less adaptable to internal or external forces, as it loses its ability to counter and resist these forces. This can lead to imbalances in the whole system.

These conditions can lead to painful syndromes, faulty movement patterns, overall fatigue, reduced performance, poor neuromuscular control and stiffness.

Strictly speaking when we say ‘release’ the fascia doesn’t actually do this. It is the reorganisation of the connective tissue system via the regulation of the nervous system through mechanical stimulation (massage) that in turn alters the general tone of the system. The ease of movement that follows is what one might attribute to the ‘release’. Fascial techniques works by facilitating:

- Increased blood flow

- Increased endocrine function

- Improved sensory-motor responses

- A general feeling of relaxation, by regulating both the conscious & non-conscious aspects of the nervous system.

- Improved motor function and strength

With the Integra Therapy approach to MFR and it interventions, there will always be a palpable and IMMEDIATE CHANGE to how you feel and move. You will generally experience less pain, feel more ease and embody more integrated movement. Because of the modulation of the nervous system, you often experience a sense of relaxation during and after the treatment, which after some time can give you a sense of invigoration and increased energy.

Get in touch to book a session at Integra Therapy.