Perhaps home is not a place, but simply an irrevocable condition

James Baldwin

I’m reflecting on home. What does home mean to me? What does it feel like to ‘be’ home? I feel at home most when I…?

My journey in the last 18 months has been circling around these questions, as my life has drastically changed. Inevitably, not only the change in my physical surroundings has come into consideration, but so too has this question been knocking on the door of me; my personhood, my body.

My body as my first home?

What is asked of me, if I consider this to be true?

A few days before writing this post, I noticed that it is Audre Lorde’s birthday. For those who do not know Audre’s work (I urge you too!), she is a black, lesbian feminist, warrior poet in her own words. She would’ve been 88 years old, 2 years older than when my own mother passed at 86. Her words, like my mothers resound and echo in me repeatedly at different times and in different ways.

In The Cancer Journals, she writes; “… the transformation of silence into language and action is an act of self-revelation and that always seems fraught with danger”

“… the transformation of silence into language and action is an act of self-revelation and that always seems fraught with danger”

In this reading, I see this silence represented by the body – a ‘silence’ we neither listen to or pay close enough attention to. In our culture, we are not conditioned to listen; perhaps we lack the skills, often we are numb- we have disconnected and are dis-embodied from our felt sense of ourselves and often our emotions. We do this for many reasons; for safety, survival, unsure sometimes of how to take the next steps.

Usually, we begin paying attention when we experience pain, unpleasant sensations or our functional capacity is restricted in some way because of this. But what if outside of these common experiences that we may label as dysfunctional, are we able to access ‘information’ from the body that can offer us more by way of choices to recognise how we ‘are’ and thus how we might act/behave?

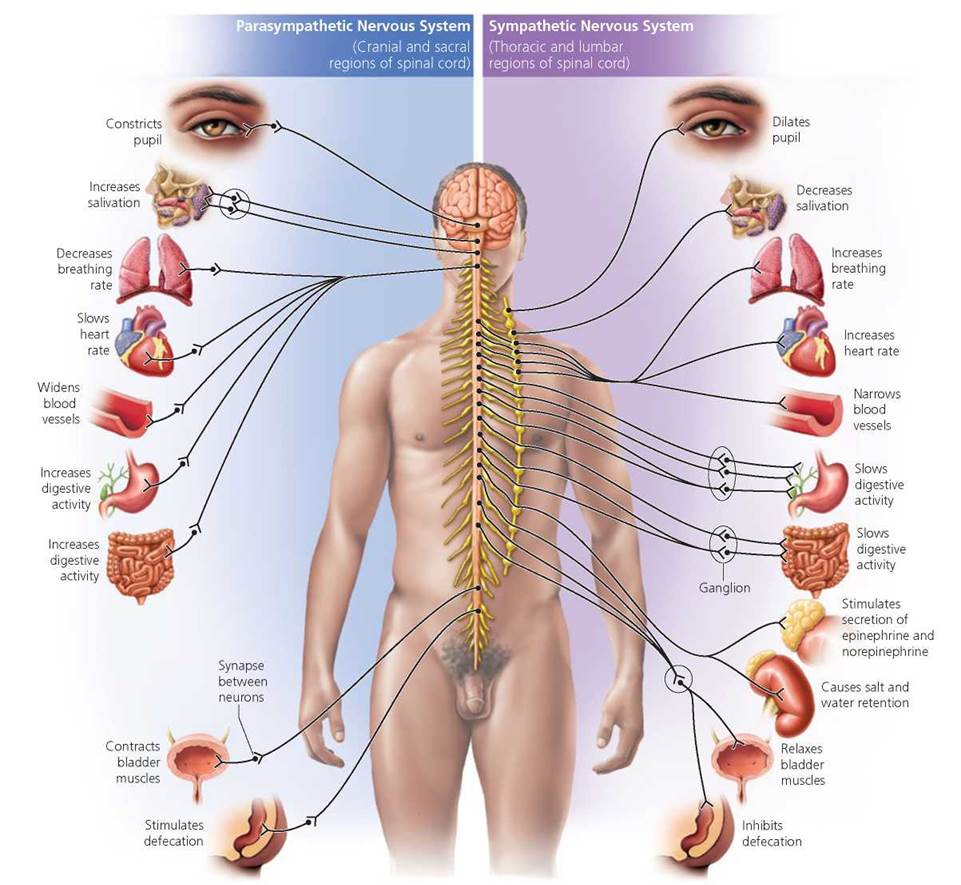

The body has its own languaging- through sensation, urges, impulses – it is preverbal and can arrive as an image and/or a symbol. The more scientific term to understand the ability to sense what the internal state of the body is, is called interoception. It is the nervous systems capacity to detect the processes of our visceral, internal processing (such as wanting to use the bathroom, have sexual urges feeling hungry, thirsty, nauseous, cold or hot). You may think that it is linked to our basic physiological mechanisms that help us as an organism survive.

Connecting to these sensations, urges and impulses is the basis to which we formulate and name our emotions, which in turn helps us to understand ‘how we are’ in any given moment. This often isn’t easy to identify and name what precisely we are feeling and this is the part where we understand we are not conditioned to connect to our feelings as it can be argued in these contemporary times, feelings or our emotions are not to be relied on. The point here is it isn’t either/or, cognition versus emotions, but rather integrating and utilising all the natural capacities of our humanity to discern how to make the choices that are right for us.

As a marginialised person… this embodied seeing can be particularly challenging as ones self-image can be distorted because of the internalisation of racist tropes and stereotypes that have been culturally normalised, which in turn shape the image of ourselves.

My work with clients as a somatic educator and in my own practice, I have understood it can be daunting to look and explore deeply into the body; confusing even- with all of the contradictions and complications of who we are and to witness what is there in our embodied experience. This ‘seeing’ may reveal parts of ourselves that we are ashamed of and exposure to this may risk a voice of judgment, scrutiny, challenge or even shame.

As a marginialised person racialised as Black and with other people who identify from the Global Majority, this embodied seeing can be particularly challenging as ones self-image may be distorted because of the internalisation of racist tropes and stereotypes that have been culturally normalised, which in turn shape the image of ourselves. This is also true of how we attempt to fit our bodies into schemas that society deems as valuable; whether you are old, fat, thin or express degrees of ability and so on. If it doesn’t fit the accepted societal norms, then it is deviant or as seen as less valuable in some way. It takes effort, practice and solid critical reasoning to undo these social scripts that historically have been designed and perpetuated to dehumanise certain bodies over others.

Lama Rod Owens, a Bhuddist teacher asked this beautiful question in his ‘Love & Rage’ course I’m taking at the moment; “What is your body’s story?” What a beautiful question? In considering this, I’m giving myself such a wide girth and space to allow thes story of my body to emerge, rather than me continually imposing my own narrative on or about it.

This process of embodiment is a way to re-humanise and accept who we are in all our complexities, nuances and differences. As bell hooks says in ‘All About Love’, the practice of acceptance is the beginning of self-love. Acceptance for who we are, although not without its difficulties or sometimes heartbreak, it is a step that can lead to a more enriched life where self-compassion can begin to blossom.

So perhaps I can find home in my body; listening to its voice through the veil of silence; to find language and right action from that place. An utterance of truth- a declaration of love- a step towards acceptance. A move towards freedom, not just me but for all beings.

For my body only longs for that of my own gaze; it’s the one that really matters most, so I can return home.