Recently I’ve had a string of clients who have come to me with issues that don’t normally fit into the musculoskeletal physio’s lexicon of conditions to treat, ranging from panic attacks, insomnia and a vague diagnosis of prostatitis (inflammation of the prostate) and chronic inflammation of the bladder. In all cases, what was common to each of them was the fact that they all experienced an increased amount of stress either from the ‘condition’ itself or the fact that they were so anxious for a diagnosis to explain their symptoms that they over-dosed on information on the internet searching desperately for answers.

In each of these instances I asked them what they thought they needed to help them at this time. And without fail the resounding answer was ‘to reduce my stress.’ So how can a physio help in reducing people’s stress and anxiety levels?

Firstly, I think I should say that this is perhaps not what most people think is in the skill set of a musculoskeletal physiotherapist, but one couldn’t be further from the truth. At its base, physiotherapists traditionally have been trained academically and clinically in a variety of medical disciplines that address a multitude of clinical issues including respiratory care both in the acute and chronic setting. Not only this, we have been groomed to have excellent observational and assessment skills to detect where dysfunction and maladaptive movement patterns occur. In this case, although long departed from the respiratory discipline, my specific interest and training in yoga and contemplative practices that enrich the art of breathing, self-observation and use techniques that foster a more relaxed state, have helped me maintain those skills.

Why stress over the stress?

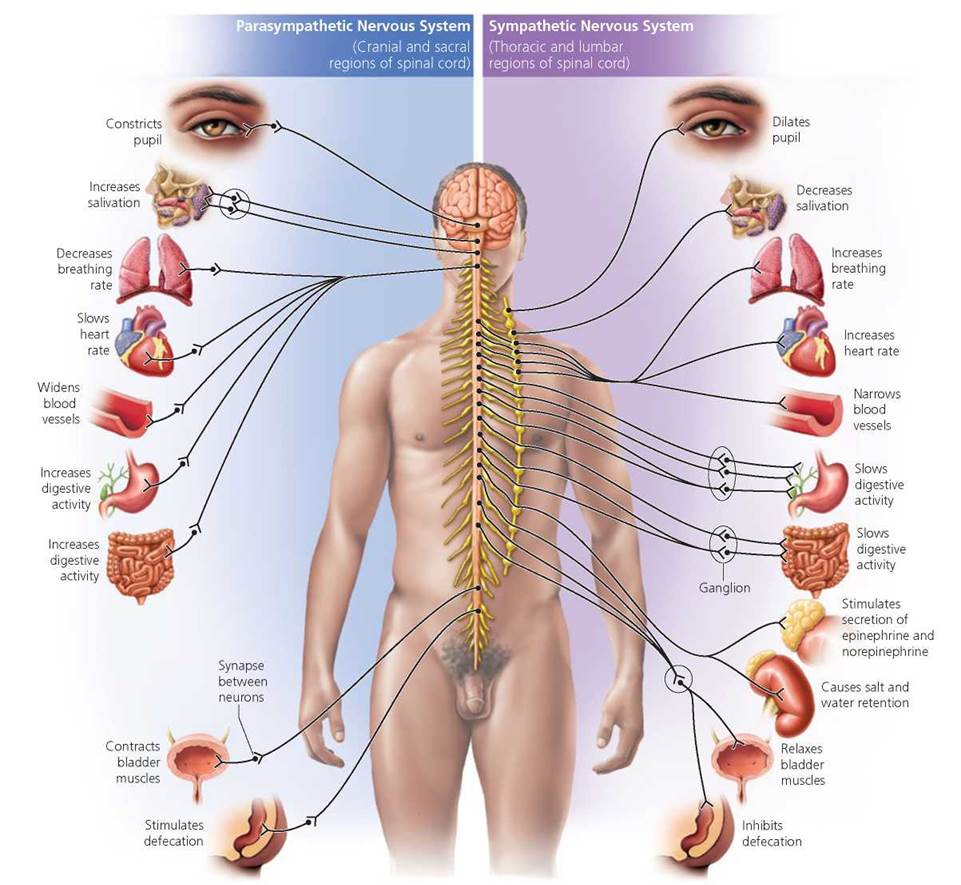

Firstly we need to appreciate that stress is a normal response of the body. In fact it is a necessary trigger to protect the body and let us know how and what to respond to appropriately. This is what is known as self-regulation and it’s our body’s ability to do this constantly that is crucial for our health and wellbeing. Typically we are familiar with the adage ‘fight or flight’ which is the response that utilises adrenaline (hormone released from the adrenal glands) as an immediate response to perceived danger. So as modern humans, we would either run from the unleased pit bull on Hampstead Heath or stand to face it head-on! It is one branch of the body’s nervous system (autonomic nervous system – ANS, see Fig.1) that works without you consciously making a decision in that process – which is really useful as it would require having super-human fast reactions and attention to be able to monitor and control all of those incoming signals in order to protect your body!

The branch of the ANS, the sympathetic nervous system controls our stress response through the organs and tissues around the body. When your system is under psychological or physical stress the sympathetic system becomes dominant in order to release energy to the tissues so you can respond appropriately to protect yourself from the perceived threat or uncertainty. Even in relatively normal stable conditions, the sympathetic system is more dominant and maintains a low level of physiological arousal (Thayer & Brosschot, 2005). On the flip side when the body needs to return to a more restful state it utilises the other aspect of the ANS, the parasympathetic nervous system which inhibits the stress response migrating the system to a more ‘rest and digest’ state (Fig. 1). The parasympathetic system has the opposite effect to an adrenaline rush in a stressful situation and this is what we want to promote when we target stress or anxiety.

What can be done to reduce stress in this setting?

One of the simplest and most accessible ways one can reduce ones stress response is by using the breath. There are of course many other ways at our disposal to reduce stress; activities that we enjoy engaging in, exercise, listening to or playing music or an instrument, walking in the countryside, reading etc. However the breath is one of the most potent influencers on the brains output to all the other physiological systems in the body. Extremely sensitive chemoreceptors (chemical receptors) in the brain detect changes in the mixture of gases dissolved in the blood and respond by sending signals via the ANS to either increase or decrease the heart and respiratory rate and accordingly, as well as effecting other systems of the body such as the endocrine system. In another blog in this three part series we will examine the effect of breathing on the fascial or connective tissue system. By working with the breath you have a very powerful means of controlling how you psychologically and physically respond to a given situation.

Here is what to do – Simple exercises you can do to help with stress and anxiety

It’s useful to be able to spot if you think you are anxious or under undue stress which we won’t go into here but this will be part of this three part series on stress. However, even if you don’t think you are, these are excellent techniques that you can use if you need ‘down time’ or want to just ‘relax and take time out’.

All you need is 10 minutes, a quiet comfortable space and YOU!

Step 1 – Noticing

Find quiet, comfortable, warm environment away from any distractions like the TV, small children and make sure your mobile devices are switched to ‘silent’ or off. You can dim the lights around you to reduce the light hitting the back of your eyes, encouraging a less aroused state. Find a lying position on your back, either on a yoga mat or equivalent or on a firm bed. Have your knees bent so your feet are flat on the floor (you can place a pillow under your knees to ease any pressure on your lower spine) or straight out in front of you. Place one hand over your chest and the other between your navel and imagined or actual bra line.

- Now take a moment to notice all the contact areas of your body on the surface that supports you. Each side or body part may feel different from each other and this is quite normal. The idea here is not to make a story about ‘why’ it is as you find it, but rather taking in and openly accepting things as they present themselves.

- Also notice the movement of both your hands as you breathe in and out. Do they move in the same way at the same time? Are you breathing in one area more than another? Often people don’t feel that they are breathing ‘properly’ and it could be that you feel hardly any movement in your chest or they don’t breath fully into the lungs and are only expanding the top of the chest with shallow breathing.

- You should notice that as you breathe in, the chest and stomach move up and outwards, the hand over your belly will move first only a fraction of a second before the other hand on the chest moves. And as you exhale both your chest and stomach should gently fall back towards the spine.

- Notice as you breath the sensations around the back, sides and top of the rib cage by your collar bones, can you feel these areas move too?

Repeat this a few times to familiarise yourself with the motion of normal relaxed breathing and discover what is true for you.

Step 2 – Taking a deeper breath

- Now take a full breath in and exhale out. Repeat this a few times to familiarise yourself with this movement, remembering to keep as relaxed as you can; through your shoulders and arms, in particular around your head and neck. This shouldn’t be hard work.

- Notice what happens to the movement of your belly-hand and your chest-hand. Do they move in the same way? Can you feel now more of the back, sides and top of your chest? Using your imagination as you inhale, can you begin to fill the base of the lungs, then the middle of the chest and then right up into the apex of the lung as your collar bones broaden? This is known as a ‘yogic’ or ‘three-part’ breath that enables you to use the full capacity of the lungs.

- Notice if you feel you are not breathing into a particular area of the lung, for example into the base of the lungs. Can you direct your attention to that area visualising the air travelling there and actively inviting the breath to go there? What does that feel like?

Repeat this 10 times and return to relaxed breathing. How does the body feel now?

Step 3 – Controlled inhalation and exhalation

If you are comfortable with Steps 1 & 2 then you can progress to this stage.

- This time remembering to keep as relaxed through the body as possible, inhale for a count of four counts, then notice a slight natural pause at the top of the in-breathe and then exhale for a count of six, again noticing the slight pause at the end of the out-breath. Repeat this cycle 5 times and then return to normal relaxed breathing. How does the body feel after that sequence?

- If you’re comfortable you can repeat this set 2 or 3 times in total and/or extending the inhalation to five counts and exhaling for seven, resting to observe how the body is after each set.

Extending the exhalation is the key here as it serves to increase parasympathetic output and reduces the general tone of the tissue (i.e. you encourage a more relaxed response in the body). It also ensures naturally that you are ready to begin inviting another breath in to begin the cycle again. Many people who suffer with anxiety feel they are not getting enough air in and this increases their stress, where they begin to over-breath which in turn compounds their sense of panic. If you consciously exhale for a bit longer, the natural reflex of the diaphragm will take over and air will naturally rush in without any effort, reducing the perceived increased effort of breathing.

It’s comforting to know that by employing your breath in a more conscious way acts as a potent regulator of how you think, feel and thus behave. It’s free; it’s always there when you need it and wants to help you live a life less stressful. Go on; why not give it a go?

Next time in part II of this three part series we’ll be looking at how you might identify the signs stress and anxiety.

References

Thayer, J. F., & Brosschot, J. F. (2005) Psychosomatics and psychopathology: looking up and down from the brain. Pyschoneuroendocrinology, 30, 1050 – 1058.

Comment (1)